Hanson Interview: 'This Time Around' at 20

43

43  44

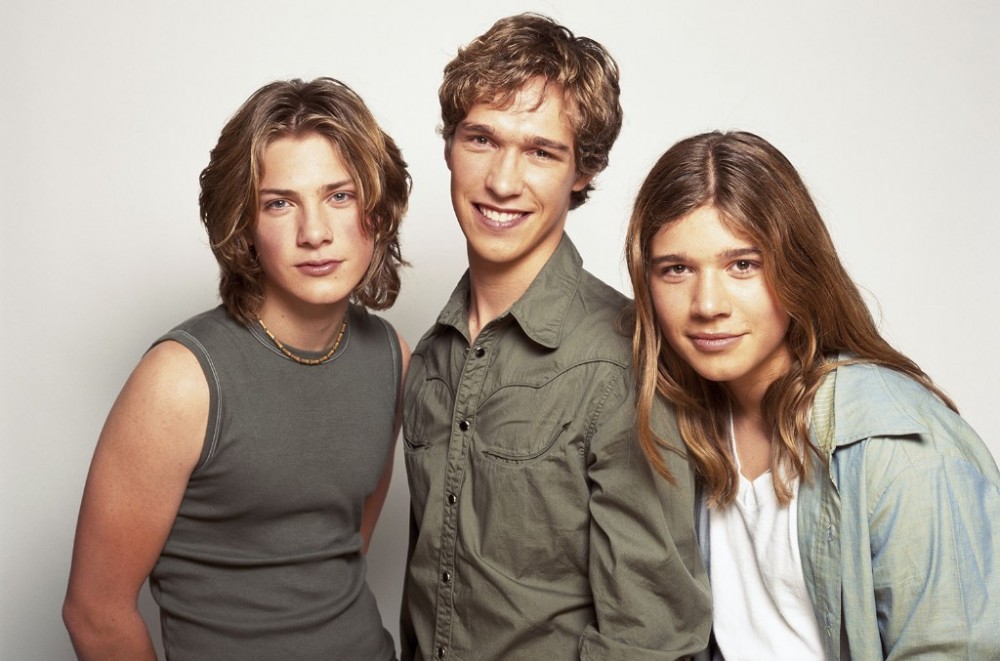

44 Following our Streets Talkin staff-picked list of the 100 greatest songs of 2000, we’re writing this week about some of the stories and trends that defined the year for us. Here, we look back at This Time Around, the stellar second from Oklahoma brother trio Hanson — who were the biggest all-male pop group in America in 1997, but by 2000 had priorities that didn’t include competing with *NSYNC and the Backstreet Boys on TRL.

And we won’t go down. It is the refrain of the title track to Hanson’s sophomore album, This Time Around, but it is also a lyric — like many on that record, which celebrates its 20th anniversary this May — that speaks to a larger narrative of fighting for something you believe in.

After breaking out with 1997’s Middle of Nowhere — an acclaimed collection of funk-tinged pop-rock that included the Streets Talkin Hot 100-topping smash, “MMMBop,” as well as subsequent MTV hits “Where’s the Love” and “Weird” — Isaac, Taylor, and Zac Hanson looked to further establish themselves artistically on their next effort. A second album is daunting and pivotal for any band, let alone when it follows up an enormously successful major label debut that sold 10 million copies worldwide, and generated massive fan hysteria in the teen-pop golden age of the late ‘90s. What Hanson had to grapple with, though, was being signed to a big record company that did not understand the kind of band they are — and was not invested enough to try to.

As such, This Time Around stands as an important album for the brothers — the approach they took and the type of music they made on the set would go on to be a foundational stone in their path over the next two decades. Bluesy pop-rock cuts, meticulously crafted. Joyful. Pensive. No co-writes. Sonic collaborations were decided choices with like-minded players like John Popper and Jonny Lang, whom Hanson regarded as peers.

Against the biggest pop albums of the early 2000s, from groups like NSYNC and Backstreet Boys — which defined the era’s sound with splashy production, steeped in electronic and hip-hop influences — This Time Around stood out for eschewing the trends, in favor of classic three-piece rock band arrangements and thoughtful songwriting. It felt distinct and lasting. It still does.

While the record did not have nearly the commercial response that Middle of Nowhere did, it was received well critically and enjoyed a couple of moderately hit singles in the top 20 hit title track and internationally successful “If Only.” But, more than anything, it set up the band to have an enduring career on their own terms, where they have maintained a prolific output and a dedicated fanbase. What’s more, they’re still together in the same lineup 20 years later, while nearly every other pop group from the period has either broken up or turned over membership.

For Hanson, This Time Around was both a challenge and a statement. “It wasn’t about bucking the system,” frontman Taylor Hanson explains to Streets Talkin over the telephone from Tulsa, Oklahoma. “It was about continuing to stay the course. And I think that is what has been consistent with our work. Staying the course.”

Below, Streets Talkin speaks with Taylor about This Time Around, how it nearly ended up being produced by the late Cars legend Ric Ocasek, and how the album continues to illustrate the band’s enduring ethos.

There is an emphasis on themes like morality and hope on this record, especially with songs like “Save Me,” “A Song to Sing,” and the title track. Were there any particular experiences that contributed to those?

It was a time where we were charting our course in a deeper way. And, in some respects, surviving having success can be just as hard as surviving failure. You’re staring down a new type of pressure — which is the pressure of expectation and the expectation of you to fail. And we were also experiencing huge turmoil around the team that we worked with, from the record company merger [with] PolyGram, Universal — losing a lot of our team, transitioning, and just not knowing where we would land. And, when this record came out, who would be with us.

For me, that album was so much of looking down the barrel of people expecting that we didn’t have more to say, that we would not be a deeper artist behind that initial introduction. And so, there was a sense of fight, a sense of challenge, a sense of withstanding, and overcoming adversity. “This Time Around,” that song depicts being, literally, in battle with the extremes of risking your life for something. But the metaphor of being willing to sacrifice or put your life aside for something you believe in — I mean, that’s what that whole season felt like.

The band, of course, later had a huge struggle with the label — which was documented in your 2005 film, Strong Enough to Break — before you walked away to start 3CG Records. What external pressures did you have at this point, in terms of what the album should sound like, to cater to the type of pop music that dominated the music landscape at the time?

We were surrounded by a lot of folks that just wanted something to be successful. We did have lots of suggestions — because we had pop success, quote-unquote — that we should work with a pop producer, or someone that was oriented towards boy bands and things like that. So, we proactively sought out meetings with all the collaborators that we wanted to work with, and ended up meeting with some of the most incredible producers around — Ric Ocasek being one of them. We actually started the record with Ric. And that was the way we pursued it, was to say no [to indulging pop trends] from the beginning.

We were going to proactively engage people that nobody could question the qualities of, from a rock and roll point of view, from an organic music production point of view. And we were also really proactive about writing and being the writers — and we’d always been the writers, but we certainly had done a lot of co-writing on the first record.

[Working with Ric] was an awesome experience. That’s the one not-told-much stories of that record. We got into the studio and did two songs with him, and I think that was probably the moment when we realized just how much of an uphill battle we were going to have. And the work we did with Ric, we were really excited about, and we knew it had potential to create an album with an entirely different sound to it. But we were not going to have the support of the label alongside us. So, that was a clear indication of the fact that we needed something that had history [with us] and we could deliver a record that everybody went, “This makes sense, because this is something that’s been done before.” So, we pulled in our producer that we worked with most of the first record, Stephen Lironi.

Did any of the songs with Ric make it to the album?

No, they are not there. They are currently archived. Maybe they’ll find their way out at some point. But we did the song “Smile” with Ric, and he loved that song. And, you know, that sort of garage rock, jangly guitar-driven sound, I think we would have leaned more in that direction on the final record if Ric had been the main producer on it.

This Time Around was critically successful, but you mostly stayed away from the Total Request Live circuit, while pop stars like NSYNC and Britney Spears were putting up historic sales numbers. Was that a conscious decision, to avoid that scene?

As far as who we are as artists and what we were putting out, that was, of course, conscious. That record got a lot of attention and a lot of acclaim as it broke out, but, ultimately, the impact of [the merger] really took shape once the record was released.

But I think that one of the most important things was continuing to get out on the road and really focus on the live show, and the relationship with the audience. And we, also, were seeing something unique that others outside of our core couldn’t really see, which was the online fanbase. We began to see a real community develop. And community that is not just about the songs, but about people connecting to each other.

We were never saying, “We don’t want to sell a bunch of records” — because, you know, we sold a lot of records. And you want to be reaching as many people as possible. I don’t think it’s about shunning popularity, but it’s about starting with who you are and positioning yourself so that, when you are successful or when you fail, you’re doing work that you’re proud of.

You guys have always maintained such strong autonomy over your music. And it’s interesting because, historically, there are so many stories regarding label politics about artists who are pressured to make certain kinds of music to fall in line with a manufactured image. How did you manage to avoid all that? Was that autonomy something difficult to hold on to, considering how young you were?

It’s difficult at any age, to balance. That’s true, I think, just as an entrepreneur — if you have a vision and a product that you see something in that is not necessarily obvious to everyone, you’re faced with the question of how much to be flexible and how much to stick to your gut.

As many challenges as we have had, many have had much worse. We’ve had an audience that we’ve been able to reach and we’ve learned through a lot of adversity. And the one thing we have maintained is that, no matter what, the work that we put out is something that we know we believe in. And that helps sustain you through high and low. And I would encourage people, in any field, to listen to that part of our story, which is that when you believe in it and when you are proud of it, success is already yours.

The album really begins to dig into those vintage textures that have become a hallmark of your music. “In the City,” for example, feels like a charged up Allman Brothers tune. Do you remember what you were listening to when you were writing?

On our first record, it was so much ’50s and early ‘60s soul music, rock and roll. And the transition was beginning to discover more Three Dog Night, later Beatles, AC/DC, and The Cars. U2. I remember our first manager saying to me, “I think once you’re an adult, I think you’ll have more of these qualities like this guy Bono.” So, thinking about his range and the type of singer [he is], his upper register.

We were [also] listening to the Black Crowes and Red Hot Chili Peppers. Because, remember, we’re still ‘90s kids, so we were also keeping up with alternative rock bands and melodic pop-rock bands that were happening in real time, too.

There are some fantastic collaborations on this record, as well. John Popper from Blues Traveler on “If Only” is one, with that wild harmonica solo. What was it like working with him?

The funny thing about John on that particular record is the harmonica part which I play was initially the impetus for asking him. That “ba da da, da da da da” rhythmic part made us think, “Wow, we should have John come play on this” — and we assumed that he would take that part and he would change it or better it, of course. It was almost like the part that I was playing was too dumb for him to play. He never replaced the core hook because it was too straightforward. So, he did the solo and all the other parts ended up being me.

But watching him play is incredible. I remember asking him, “How did you possibly develop this style and this skill?” And he’s like, “Well, you know, if you get 10 years in your mom’s basement doin’ nothing else, you’d develop that skill too.” [Laughs.] I get that [he was] being funny, but there is so much truth in that. If you focus on something with little interruption, you’ll probably develop something unique from it as well.

“Dying to Be Alive” stands out, too. It feels like a gospel song, especially on the chorus with the choir. How did that song come together?

It really felt like we were going to be challenged to take whatever risk was necessary, to throw ourselves on a track, so to speak, for this record to happen. “Dying to Be Alive” was a sort of way of saying — one, it is a spiritual song, it is talking about something more eternal. And also, it’s speaking to this idea of dying to yourself, dying to what you think is life in order to find something greater.

The sound of that song was fully gospel. That steps pattern, that is a gospel structure. We were talking about how to replicate a great choir sound, with an arranger that really understood song structure and could meld with a rock and roll band. And this group that we pulled in was led by Rose Stone, Sly Stone’s sister, former member of Sly and the Family Stone. She’s the voice that you hear belting, “dying to be aliiiiive.” She’s amazing and really just a beautiful soul. They’re just pros. We spent the day on a session, and there’s only six in the group, and we did several multi-tracks to build up to a large chorus and Rose threw down and it was so natural. I think the sound of that song is joy in spite of adversity.

There’s a lot of dark themes in all of our work, but we’re always seeking an answer, and seeking hope, and seeking some sense of meaning and purpose of aspiration. I think that sense that it’s worth fighting. Whether it’s a moral conundrum, or “Can I pay the bills?” or “Do I have the energy to get up tomorrow?” Or “Can I do the right thing for somebody?” or “Can I stick to my guns when I have something I know I believe in and that is being challenged?” Or “Can I just survive the day?”

I mean, these are all questions I really have. And so, the question is not are there challenges — the question is, how do you handle them?